Written by Stan Ingersol

From his column Past to Present

Monastic communities, Wesleyan class meetings, congregational life, Sunday schools, and social welfare ministries all reflect aspects of Christianity’s social impulses. Wesleyan Methodists and Free Methodists developed from the anti-slavery crusade. The Salvation Army was oriented completely toward the poor. With other Wesleyans, Nazarenes have shared an ethic of social welfare.

John Goodwin, the fifth general superintendent, articulated this principle: “Pure religion always has... two sides, purity and service. To neglect service in the welfare of others is to demonstrate a lack of purity. Holiness people should be preeminent in social service. This is what chiefly characterized the Early Church—their untiring service to bless their fellowmen and care for their widows and fatherless children.”1

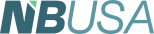

H. D. Brown, the first district superintendent, co-founded an orphanage and maternity home in Seattle. Evangelist Oscar Hudson operated an orphanage in Texas, and Santos Elizondo founded another one in Juarez, Mexico. She was pastoring the Juarez congregation and caring for 40 orphans when she died.

Nazarenes took over the Peniel Orphans Home near Greenville, Texas, and established a General Orphanage Board to provide support. Other church-related orphanages operated in Oklahoma, Swaziland, and India.

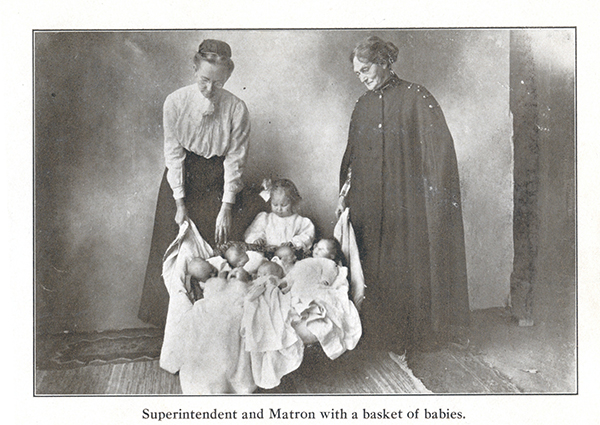

Jernigan, founding pastor of Bethany, Ok.,

First Church, was director of the Nazarene

home for unwed mothers in Bethany

for almost a decade (ca. 1910).

City mission work was primarily evangelistic but had other objectives, too. Mary Lee Cagle entered saloons to plead earnestly with the girls about adopting a more humane life. J. T. Upchurch and Johnny Hill Jernigan urged girls to leave brothels and offered places of refuge and redemption. One angry brothel manager fired a pistol at Sister Jernigan as she led a young prostitute out of a “house of ill repute.”

Other city missions assisted the homeless and addicted. The Kansas City Rescue Mission (now Shelter KC), founded in 1950, has endured for 70 years by adjusting to changing needs.

Maternity homes sprang from the nineteenth century’s “purity crusade,” which taught sexual abstinence until marriage, opposed the “double standard” that winked at the sexual transgressions of men but punished women, and aimed to restore the reputations of those who gave birth out of wedlock. Rev. J. P. Roberts, founder of the Rest Cottage in Pilot Point, Tex., put it thus: “After they are redeemed… we that are saved and sanctified never look upon them or think of them as lost characters, but we love them and admire them.”2

Nazarenes operated other maternity homes in Kansas City, Mo.; Arlington, Tex.; Bethany, Ok.; Memphis Tenn.; Lake Charles, La.; and Oakland, Cal.

Medical missionaries also ministered to physical needs. The church deployed nurses to mission fields early on, and Nazarene hospitals opened in Swaziland and China in the 1920s.

Dr. David Hynd developed the hospital in Manzini, Swaziland. A surgeon from Glasgow, Scotland, he took construction manuals to Africa and oversaw basic construction. He then supervised the hospital for nearly 40 years and founded the Swazi Red Cross.

Rev. C. J. Kinne, founding manager of Nazarene Publishing House, organized the Nazarene Medical Missionary Union to raise funds to build Bresee Memorial Hospital in China, where he also was the construction manager. It opened in 1925.

Other Nazarene hospitals appeared in India and Papua New Guinea. Each hospital was the hub of a wider network with programs that trained nurses, operated detached clinics (like a leprosy sanitarium in Swaziland) and mobile clinics that took medical services to remote locations.

at Endengeni Mission Station, 1940.

Social ministries assumed new shapes in the 1970s, coalescing around the work of Nazarene Compassionate Ministries International and NCM USA/Canada.

The Haiti famine (1975) and Guatemala earthquake (1976) generated interest in the church’s new Hunger and Disaster Fund. Broad interest in Christian social work was evident when nearly 500 participants registered in 1985 for the very first Nazarene Compassionate Ministries Conference.

NCM’s ministries grew to encompass disaster relief, child sponsorship, economic development, and ministry to those with AIDS.

Such ministries align with the Lausanne Covenant’s clause on “Christian Social Responsibility,” affirmed by a global gathering of Evangelicals in 1974. Acknowledging God’s desire for social justice, the Covenant notes:

- The message of salvation implies also a message of judgment upon every form of alienation, oppression and discrimination, and we should not be afraid to denounce evil and injustice wherever they exist. When people receive Christ they are born into his kingdom and must seek not only to exhibit but also to spread its righteousness in the midst of an unrighteous world.3

Stan Ingersol is manager of archives for the Church of the Nazarene.

1John W. Goodwin, “Holiness Children,” Herald of Holiness (Nov. 10, 1920).

2J. P. Roberts, Pentecostal Messenger (Oct. 1, 1912): 6.

3C. Rene Padilla, ed., The New Face of Evangelicalism: An International Symposium on the Lausanne Covenant (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1976), p. 87, and see Athol Gill’s exposition of clause 5, pp. 89-102. Also see: www.lausanne.org/covenant