Written by Stan Ingersol

From his column Past to Present

New Testament Church of Christ

(NTCC) in Milan, Tennessee

(l to r): Elliot J. Sheeks, Mary Lee Cagle,

and Donie Mitchum.

Through mergers with other holiness

groups in the early 20th century, the

NTCC would become part of the

Church of the Nazarene at its

founding in 1908.

The story Timothy Smith told in Called Unto Holiness (1962) seemed straightforward enough: Robert Lee Harris “set in order” the first congregation of the New Testament Church of Christ in Milan, Tennessee, during the summer of 1894, but died soon afterward. His widow, Mary Lee Harris (better known later as Mary Lee Cagle) and two other women picked up the work, prevented the new church from dying, and extended its ministry by planting new congregations.

In the 1980s, though, I discovered a more complex story had been hidden from view. None of the Nazarene sources had talked about it. Going through the pages of The Milan Exchange, the city’s local newspaper, I discovered three women had come to Milan in the late spring of 1894. They were Susie Sherman, Emma Woodcock, and Grace George. Two of them were preachers.

Susie Sherman had begun preaching at age fifteen on the streets of St. Louis, where her father, Rev. C. W. Sherman, led the Vanguard Mission. Later, Susie had joined the Pentecost Bands, a network of young people's bands within the Free Methodist Church. Susie had continued to preach for them.

The women came to Milan to assist Harris in his revival there. And, because he had tuberculosis and often felt too ill to preach, Sherman and George took turns filling the pulpit when he was unable to do so. Since services were conducted daily under the revival tent, their presence was a real boon to Harris and kept the revival’s forward momentum going.

There is more: in the Nazarene Archives, there is a list of charter members of the New Testament Church of Christ. It has thirteen names, including Sherman, Woodcock, and George.

In time, the visitors moved on.

Susie Sherman died a few years later in Africa, the young wife of Harry Agnew, the founder of Free Methodist missions in Africa. Woodcock also died abroad, as a teacher at a mission in India operated by the Vanguard Mission.

The work of these ladies continued, though, in the ministries of other women whom they inspired: Mary Harris, Donie Mitchum, and Elliot J. Sheeks.

Mitchum functioned as a lay preacher for nearly five years and helped organize several congregations. Harris and Sheeks also were lay preachers for five years and then were ordained to the ministry in the same service in 1899. They continued in active ministry through the 1930s. Harris planted the first Nazarene congregations in West Texas and was the effective founder of the Abilene District there. Altogether, she planted nearly 30 churches, including Lubbock First. Sheeks was a pastor until 1918, then moved to Kansas, where she taught religion at Bresee College in Hutchinson until she retired.

The hidden history of the three visiting women from the Pentecost Bands underlines the importance of role models in affirming the call and ministry of women. We don’t know, for instance, whether Harris would have activated her call to preach without the gentle nudge given by the examples of Sherman and George.

We also don’t know where Phineas Bresee derived his progressive views on female ministry. One assumes he was acquainted with the literature on the subject that was current in his day, including works by Phoebe Palmer (The Promise of the Father, 1859), Catherine Booth (Female Ministry; or, Woman’s Right to Preach the Gospel, 1859), and Free Methodist founder B. T. Roberts (Ordaining Women, 1891).

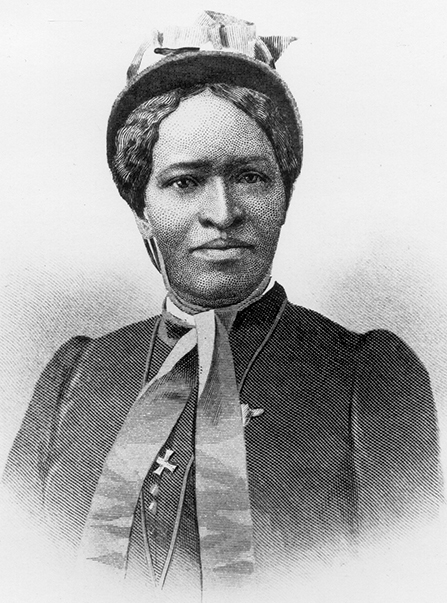

whose ministry had an influence

on Phineas F. Bresee.

But Bresee, too, had a role model for female ministry. It is likely Bresee first encountered the noted Black evangelist Amanda Berry Smith through holiness revivals and conventions in the Midwest sponsored by the National Holiness Association. Bresee and Smith were both leading members of the NHA, and Smith had conducted services on at least four continents and had preached before European monarchs. She conducted revival services for Bresee in 1890 or 1891, when he was pastor of Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church in Los Angeles. At the time, Bresee compared her pulpit eloquence to that of his hero, Bishop Matthew Simpson. Four years later, when the Church of the Nazarene was organized in Los Angeles, the rules for the new church permitted female preachers.

These two vignettes from Nazarene history underscore the value of role models in ministry, especially role models who challenge rigid stereotypes. Bresee challenged the race line and the gender line by bringing Amanda Smith to preach to his congregation. How many of us share his spirit in the matter?

Stan Ingersol, Ph.D., is former manager of archives for the Church of the Nazarene.